May 30th is the 150th anniversary of celebrating and remembering deceased veterans. It began in 1868 as Decoration Day to commemorate the soldiers slain in the Civil War, and later those lost in the Spanish-American, World War I and World War II. As a child in the 1950’s, we celebrated the day in quaint ways that seem almost relics from another century. I remember Decoration Day (as we called before 1971) as a more solemn and communal occasion than it seems after changing its observance from a fixed date to the end of a three-day weekend on the fourth Monday in May. Along the way, we may lost much of the communal solemnity.

Decoration Day always occurred during the most glorious weather southern Minnesota can offer. A time to honor the dead at a season of new life. The trees were leafed out, wild phlox and geraniums bloomed in the woodlands, orioles and meadowlarks trilled from the fencerows and cottonwood groves. This day meant two things important to this schoolboy: my little sister’s birthday and the last week of classes before summer vacation.

My memories of our small-town Decoration Day celebration began with the sale of buddy poppies in the Rexall drug store, the Ben Franklin dime store and other shops. Veterans of World War II sold them to raise money for comrades disabled in conflict. At the age of 10 or 11, I couldn’t explain why I bought one except everyone expected me to. Like going to church, I did it because–well–everyone else did it. It was part of being an American to wear this icon of remembrance and sacrifice.

On this day, the merchants of Janesville hung out flags and there was a parade led by the VFW honor guard carrying the American flag followed by the drill team marching along, the sun gleaming off their chromed helmets and the barrels of the Springfield rifles on their shoulders. Behind them came VWF Women’s Auxiliary and the high school band playing patriotic songs for this solemn occasion. If there were speeches, I don’t recall them but they weren’t things boys remembered.

Decoration Day meant a trip to the Janesville Cemetery on a knoll a mile east of town. In the days leading up to the celebration, families raked the ground over the graves, mowed the new grass and decorated the headstones with flowers (real or made of paper), and small American flags. Our family went to the cemetery with Aunt Faith to visit her father’s grave. On the headstones I saw many familiar surnames, the ancestors of my classmates and school chums. Even as a boy, I felt a palpable but still inexpressible link connecting me to those lying beneath the headstones.

Almost every man I knew when I was a boy had served in World War II in some capacity. Uncle Walter, our neighbor’s brother, lost an eye fighting the Japanese. Our dentist served in the cavalry (without horses), mother’s cousin was a B-24 crew chief and my uncle Rob ran an Air Force fighter communications network in China.

Mrs. Wegge, our sixth-grade teacher, prepared us for Decoration Day. I recall learning the first stanza of the famous poem, In Flanders’ Fields, written in 1915 by a Canadian soldier amazed to see the brilliant red flowers blooming in the hellish no-man’s land churned and pocked by shells:

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

The poem’s elegiac meaning made little impression on me until the summer of 1961, after I graduated from high school. I visited Flanders in Belgium as part of an air cadet exchange with other NATO countries. Belgium is one tenth the size of Minnesota and a battleground during much of its history. Flanders lies north of Brussels, Waterloo, the site of Napoleon’s defeat in 1815, lies just south of it and Bastogne, a major battle of World War II, lies to the east. During that month, our Belgian Air Force hosts showed us historic sites from many wars. We laid a wreath at the tomb of the unknown and our contingent sat atop the hull of a tank destroyed in the battle for Bastogne, sixteen years before. I returned home from Belgium amid a national mobilization for conflict with the Soviet Union over access to Berlin. War seemed very close.

The grief of the Civil War, the Great War and World War II touched virtually every American community and nearly everyone knew of a family that had lost someone. Congressional declarations of war and shared sorrow once mobilized the nation into a common effort. For 30 years, compulsory military service gave young men a common and transformative experience and every family a direct stake in going to war or opposing it.

John F. Kennedy’s call to “ask what you can do for your country” has lapsed with time. The abolition of the draft and reliance on a wholly professional military has made serving one’s country an option, a choice but not a shared responsibility. I fear this change has made us numb to the conflicts ostensibly waged for our protection. And with this disconnection, we may lose our understanding of Memorial or Decoration Day as a time of comunal remembrance.

Sound is something it’s easy to take for granted. Like the air I breathe, I take it for granted unless something stands out in the sound cloud around me. Then, maybe a noise I hear in isolation, triggers a memory. At once, the present moment dissolves, and I’m inside a past moment; it’s a spark of time as fresh and real as the original. These reverberations of the past never erode or rust or lose their power. They’re visceral, eidetic, and so penetrating that important parts of my life, my very soul, was shaped by them. It may be that my individuality and yours are defined as much by echoes as by fingerprints.

Sound is something it’s easy to take for granted. Like the air I breathe, I take it for granted unless something stands out in the sound cloud around me. Then, maybe a noise I hear in isolation, triggers a memory. At once, the present moment dissolves, and I’m inside a past moment; it’s a spark of time as fresh and real as the original. These reverberations of the past never erode or rust or lose their power. They’re visceral, eidetic, and so penetrating that important parts of my life, my very soul, was shaped by them. It may be that my individuality and yours are defined as much by echoes as by fingerprints. You may laugh, but I will swear it is possible to hear corn growing. I know I did on humid, July nights, when no breezes stirred southern Minnesota. Lying in bed, I heard the faintest of sounds outside, as if someone were tearing paper slowly and carefully to make no noise at all. But something was ripping in the lower fields. It was the sound made by leaves of corn splitting their sheaths as they unfurled in the muggy darkness. It was a ‘green noise’ that often lulled me to sleep when nothing else could.

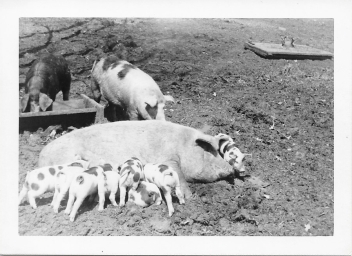

You may laugh, but I will swear it is possible to hear corn growing. I know I did on humid, July nights, when no breezes stirred southern Minnesota. Lying in bed, I heard the faintest of sounds outside, as if someone were tearing paper slowly and carefully to make no noise at all. But something was ripping in the lower fields. It was the sound made by leaves of corn splitting their sheaths as they unfurled in the muggy darkness. It was a ‘green noise’ that often lulled me to sleep when nothing else could. by a squeal. They usually fed at night, and took turns eating at the individual feed boxes covered with metal lids. In sixes and sevens, they nosed up the lids, then grunted contentedly as they smacked on ground oats and corn. When sated, each pulled his snout from the lid and it fell with a ‘clunk.’ Many nights, I fell asleep listening to grunt, smack-smack-smack, grunt. Clunk! This rhythm lasted until I left for college, and Dad sold the hogs. For a long time afterward, on visits home, I unconsciously listened for them and, when I didn’t hear them, knew a part of me was no longer resident there either.

by a squeal. They usually fed at night, and took turns eating at the individual feed boxes covered with metal lids. In sixes and sevens, they nosed up the lids, then grunted contentedly as they smacked on ground oats and corn. When sated, each pulled his snout from the lid and it fell with a ‘clunk.’ Many nights, I fell asleep listening to grunt, smack-smack-smack, grunt. Clunk! This rhythm lasted until I left for college, and Dad sold the hogs. For a long time afterward, on visits home, I unconsciously listened for them and, when I didn’t hear them, knew a part of me was no longer resident there either. whispers ‘sweet nothings’ to leaves on a summer’s eve. Like great compositions, the wind may use a caesura, a full stop amid a storm, and in the fragment of silence, I can hear an individual drop of rain fall from a leaf and strike the ground with a fat ‘plop.’ The wind talks. For those who listen, there is much to be learned from the wind.

whispers ‘sweet nothings’ to leaves on a summer’s eve. Like great compositions, the wind may use a caesura, a full stop amid a storm, and in the fragment of silence, I can hear an individual drop of rain fall from a leaf and strike the ground with a fat ‘plop.’ The wind talks. For those who listen, there is much to be learned from the wind. went to Mass. As the rural population thinned, the diocese closed the church, and it fell victim to time and neglect. I last saw it on a summer evening, shuttered but humming with the sound of bees swarming about a hole in its eaves. Only the cemetery remains but, somewhere in the heavens, the reverberations of that bell continue to ripple toward eternity.

went to Mass. As the rural population thinned, the diocese closed the church, and it fell victim to time and neglect. I last saw it on a summer evening, shuttered but humming with the sound of bees swarming about a hole in its eaves. Only the cemetery remains but, somewhere in the heavens, the reverberations of that bell continue to ripple toward eternity. purred. Yet, despite the make of tractor, their sound faded quickly with distance. Some of my deepest memories are of twilight on spring evenings, hearing my father whistling Broadway show tunes as he tilled a field for planting. As sure as the sun came up in the east, I knew his restless soul was utterly content and he wanted nothing more than to make the brown, prairie soil ready for seed.

purred. Yet, despite the make of tractor, their sound faded quickly with distance. Some of my deepest memories are of twilight on spring evenings, hearing my father whistling Broadway show tunes as he tilled a field for planting. As sure as the sun came up in the east, I knew his restless soul was utterly content and he wanted nothing more than to make the brown, prairie soil ready for seed.