I have moved my on-line writing to Substack. Weekly I post a 600–800-word story drawn from growing up on a Minnesota farm in the 1950s. That is an era now long gone and forgotten. Yet it was fruitful time in an age before cable news, the internet, cell phones and Instagram. It was anything but a digital age.

Looking back isn’t inherently nostalgic. If seen with clear eyes the past is instructive with respect to the present. I encourage you to visit me weekly on Substack. Below is a sample of what you will find:

Making Do

My father started farming minus two things essential to success: experience and machinery. Fortunately, he had determination, a 1947 Ford tractor, a small plow and an equally small disk. New farm machinery was scarce and expensive in the immediate post-war years. He had to “make do” until he could afford to buy machinery. “Making do” aptly described our family modus operandi until 1961 when my father quit farming and underwrote insurance.

We made do with machinery bought at auctions as established farmers sold their old machinery for new. My father went looking for a bargain and I sometimes tagged. The stocky auctioneer in a Stetson put on a good show. Standing on a hay wagon surrounded by men in overalls, he talked up the quality of the item at sale. After a swig from a jar, he set the opening bid and then he launched into his rapid-fire spiel.

“Ten. Gimmegimmeten, gimmeten, ten, ten, gimmeten, gimmeten, do I hear ten? Ten!” And he pointed his cane at the bidder. “Do I hear twelve. Gimmegimmetwelve, gimmetwelve. Twelve! Fifteen, gimmegimmefifteen…”

And so it went as the farmers made their subtle bids—a nod or a finger wave—and bought the mowers, plows, disks and seed drills. In our first two or three years, my father bought a second-hand grain swather-binder for $30, a manure-spreader for $115 and a corn-picker for $250.

Swather-binders have been around since the 1870s and the rusty model he bought cut our hay, wheat and oats and until the farm generated enough cash to replace it with a powered sickle bar mower and then a small John Deere combine.

Our herd of Guernsey cows would have buried us under their waste without a manure spreader, A single cow produced about 115 pounds daily! Every day, our herd dropped about 1,500 pounds. After the morning and evening milking, my father shoveled the shit into a bucket that ran on a rail down the length of the barn and outside where it dumped on a pile.

Manure had value as fertilizer and we spread it before planting in the spring or after plowing in the fall. Our “make do” spreader was a wooden wagon with steel wheels that drove a chain conveyer that dragged the manure into to the rear “beaters” that dispersed the clods in smaller bits. I sometimes rode on the spreader’s seat but avoided it on windy days because the gusts pelted me with it.

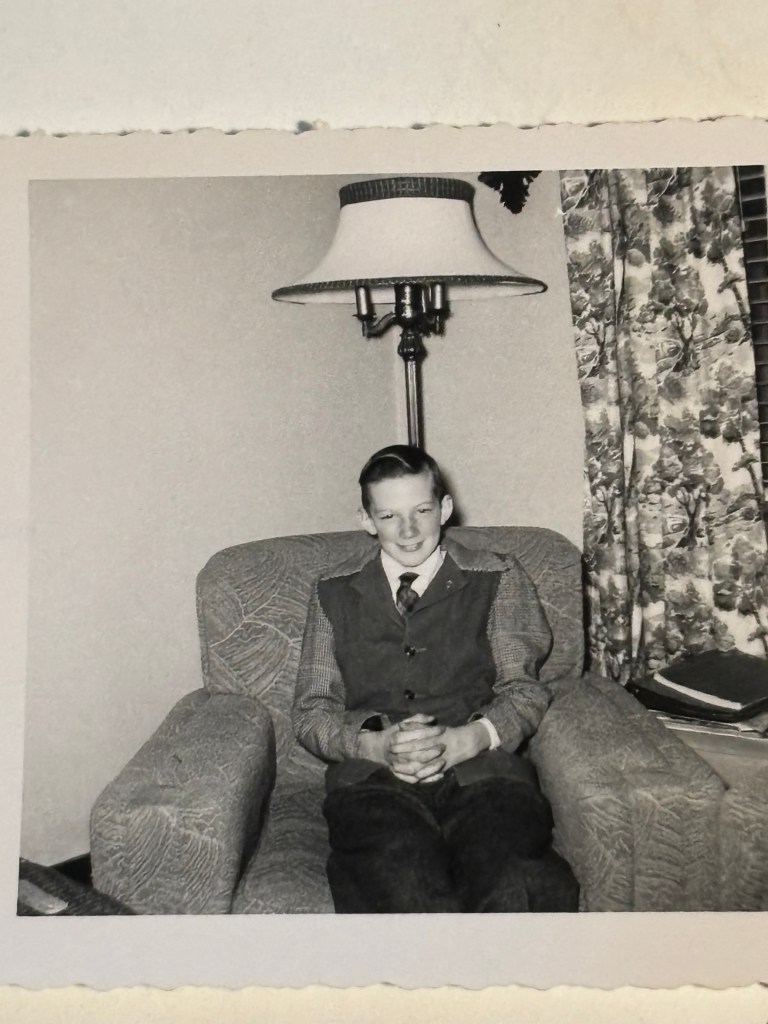

Making do also included clothing. My new “school clothes” were the affordable jeans and shirts from the Sears Roebuck catalogue. Dressy “church clothes” were too expensive but my mother knew mothers whose sons had outgrown their clothing. I was twelve and recall trying on a suit coat at someone’s house. At sixteen, I went to the high school prom in a used dark blue suit altered to fit me.

Seventy years later, frugality is still hard-wired into my psyche. The idea of buying something new because it is new goes against my grain. If clothing or a tool still serves its purpose, I keep it. And if I can no longer use something, I give it away to someone who can use it.

There is nothing wrong with “making do” with second-hand machinery, tools or clothing as long as it is serviceable. Growing up with frugality taught me that new machinery itself doesn’t make a successful farmer nor do new clothes necessarily make the man, and a good craftsman never blames his tools.