Whose Spittin’ Image?

People who knew my father often said I was the ‘spittin’ image’ of him. And there was some truth to that. We walked with similar gaits, we were similar about the eyes, though his were blue and mine were brown. Beyond that, however, we diverged. Dad was an extrovert while I enjoy solitude as much or more than company. Since the advent of DNA tests, ‘spittin’ image’ takes on a new meaning.

For a long time, I ignored the offers to send my DNA to the genealogical company to learn about my ancestry. My family tree is well-documented back to England in the 1630s. I recall my shock and disbelief when I discovered my father’s earliest ancestor (Abraham Newell) and my mother’s, (John Livermore) arrived in Boston on the same ship. They were English Puritans fleeing the persecution of Archbishop William Laud. They must have become acquainted during their three-months voyage before landing in Boston and going their separate ways and intermarried Puritan descendants in New England and New York. The last immigrant to marry into my family came from England in 1814. My parents married in 1941, uniting two families who voyaged together 305 years earlier.

I gave in, ordered the kit, spit into the tube and sealed the sample inside its mailer. Why am I spending $79 for this? I wondered. What can it tell me about my ancestors that I don’t already know? I sent it off, confident of the results: a preponderance of British DNA with soupçons of French from the invading Normans and maybe a drop from the marauding Danes.

With surnames liked Searle, Christie, Livermore, Baldwin, Cook, Eliot, Stewart, Smith, Wheelock, Wood, Douglas, Taylor and Warren, I had no doubts my family originated with the English and Scots. Searle is one of the commonest of English names–like Anderson in Minnesota. My extended family tree included only one set of Dutch ancestors and that one very recent. We came from what was called ‘good Yankee stock,’ a phrase better fitting the bull of highland cattle. What they meant was, we were white Protestants from Britain or maybe the Netherlands.

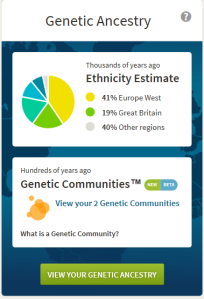

Six weeks later, when the email with my results arrived, I opened the link to see a colored pie chart before me. Things aren’t always as they seem and neither am I. A large lemon wedge—41%—said West Europe (France, Netherlands), an apple green wedge—19%—said British (English, Welsh and Scottish), and a gray wedge—40%—said ‘Other.’ That’s me? Not what I expected!

And what’s in the ‘Other?” That category included 18% Irish, 11% Scandinavian, 7% East European and 2% (possibly) Italian. In the State of Minnesota, it’s useful to claim some Scandinavian ancestry. Call it street cred. Besides, it’s good for my marriage since my wife’s great-grandparents emigrated from Norway.

What does this mean in the end? Or doesn’t it mean anything?

Regardless of what the DNA tells me about my past (and it’s fun to speculate and wonder), my identity is determined by where I live, whom I live among, the language I speak and the cultural norms that guide my thoughts and actions. You and I are creatures of the present time. Our strains of DNA entered our family lines long before recorded history when the coastlands and rivers were the crossroads for traders and raiders, for people seeking refuge from other groups or finding good land for crops. The Saxons, Frisians, Franks and Gauls settled in Britain before the collapse of Rome. Migration and trade after that deepened the mixture. The various genetic strains represent peoples and cultures that, like yeast in bread dough, are invisible but inextricably bound up with the mass of flour and water.

Unless our ancestors and immediate family lived in extremely isolated communities, it’s probable our DNA contains many contributions from varied sources over time. Were it possible (and I wish it were), you and I might look back in time to see our common ancestors and their struggles or even the moment when they received the genetic link that binds us now. I know that moment was there—is there—but we can’t see it.

How you and I see each other has more to do with culture and language than invisible DNA. Yes, we may notice differences in racial traits at first but, unless either of us is a bigot, we aren’t likely to linger for long on skin tone or the shapes of eyes and noses. We will be listening to expressions of values, ideas, opinions, humor among many other traits. You and I will know the other by our demeanor; whether we smile or glower, act kindly or harshly, with modesty or egotism. These things will quickly tell us whether we are apt to be friends.

I have no idea where my most ancient origins began. My veins don’t run with the ‘pure blood’ from any group—and it’s likely yours don’t either. Though we are free to interpret our past as we choose, there is at least one over-riding lesson we can draw from our DNA. Racial purity is a lie.

You and I probably share a relationship much closer than we may suspect because it isn’t obvious on the surface. But if we pay attention to our DNA, we can’t sustain the fiction that we are so different from others as to put them in a separate category. There is no ‘other;’ there is only ‘us.’ Our DNA makes us children of many fathers and mothers; at the level of our DNA, we are the ‘spittin’ image’ of each other.

Again, an arresting observation. Thanks, Newell!

LikeLike

Thanks, Bob. It’s always a bright day when I hear from a reader.

LikeLike