Sound is something it’s easy to take for granted. Like the air I breathe, I take it for granted unless something stands out in the sound cloud around me. Then, maybe a noise I hear in isolation, triggers a memory. At once, the present moment dissolves, and I’m inside a past moment; it’s a spark of time as fresh and real as the original. These reverberations of the past never erode or rust or lose their power. They’re visceral, eidetic, and so penetrating that important parts of my life, my very soul, was shaped by them. It may be that my individuality and yours are defined as much by echoes as by fingerprints.

Sound is something it’s easy to take for granted. Like the air I breathe, I take it for granted unless something stands out in the sound cloud around me. Then, maybe a noise I hear in isolation, triggers a memory. At once, the present moment dissolves, and I’m inside a past moment; it’s a spark of time as fresh and real as the original. These reverberations of the past never erode or rust or lose their power. They’re visceral, eidetic, and so penetrating that important parts of my life, my very soul, was shaped by them. It may be that my individuality and yours are defined as much by echoes as by fingerprints.

Living in Oaxaca, Mexico, I wake about 5:30 each morning to the sound of roosters crowing from atop a nearby house. While this may annoy some sleepers, the rooster’s crow transports me back to childhood. It’s morning once more on the farm. The eastern sky blooms and the first amber light washes across the field, infiltrates the oak tree outside my window, and falls across my bed. Roosters and daybreak are inseparable. The bravado of crowing foretells a day of unforeseen possibilities. On a farm, there is the plan for the day, and then there is what really happens. The cock’s crow reminds me of possibilities and pitfalls to come.

You may laugh, but I will swear it is possible to hear corn growing. I know I did on humid, July nights, when no breezes stirred southern Minnesota. Lying in bed, I heard the faintest of sounds outside, as if someone were tearing paper slowly and carefully to make no noise at all. But something was ripping in the lower fields. It was the sound made by leaves of corn splitting their sheaths as they unfurled in the muggy darkness. It was a ‘green noise’ that often lulled me to sleep when nothing else could.

You may laugh, but I will swear it is possible to hear corn growing. I know I did on humid, July nights, when no breezes stirred southern Minnesota. Lying in bed, I heard the faintest of sounds outside, as if someone were tearing paper slowly and carefully to make no noise at all. But something was ripping in the lower fields. It was the sound made by leaves of corn splitting their sheaths as they unfurled in the muggy darkness. It was a ‘green noise’ that often lulled me to sleep when nothing else could.

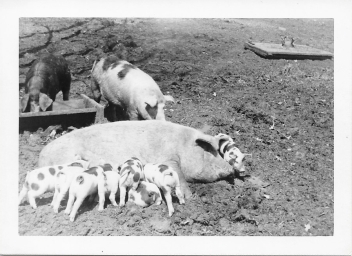

Our hogs filled an important place in my childhood soundscape of hums, thuds, crashes and swishes. Their guttural voices were as integral to my world as the acres of oats and corn, the woods, and the prairie river. Grunting hogs sang contrapuntal base notes to the roosters’ shrill falsettos. Pigs often carried on in a low, soft hum punctuated  by a squeal. They usually fed at night, and took turns eating at the individual feed boxes covered with metal lids. In sixes and sevens, they nosed up the lids, then grunted contentedly as they smacked on ground oats and corn. When sated, each pulled his snout from the lid and it fell with a ‘clunk.’ Many nights, I fell asleep listening to grunt, smack-smack-smack, grunt. Clunk! This rhythm lasted until I left for college, and Dad sold the hogs. For a long time afterward, on visits home, I unconsciously listened for them and, when I didn’t hear them, knew a part of me was no longer resident there either.

by a squeal. They usually fed at night, and took turns eating at the individual feed boxes covered with metal lids. In sixes and sevens, they nosed up the lids, then grunted contentedly as they smacked on ground oats and corn. When sated, each pulled his snout from the lid and it fell with a ‘clunk.’ Many nights, I fell asleep listening to grunt, smack-smack-smack, grunt. Clunk! This rhythm lasted until I left for college, and Dad sold the hogs. For a long time afterward, on visits home, I unconsciously listened for them and, when I didn’t hear them, knew a part of me was no longer resident there either.

The prairie wind is a maestro of sounds and moods, depending on the month and weather. A March wind has a wet smell, and roars through the bare oaks about the house ahead of a warm front. It’s a fickle wind that often produces a late spring blizzard more often than bluebirds. At the season’s other end, a November gale through these same oaks blusters like a bully, heralding the on-set of cold and darkness. In between, the wind often  whispers ‘sweet nothings’ to leaves on a summer’s eve. Like great compositions, the wind may use a caesura, a full stop amid a storm, and in the fragment of silence, I can hear an individual drop of rain fall from a leaf and strike the ground with a fat ‘plop.’ The wind talks. For those who listen, there is much to be learned from the wind.

whispers ‘sweet nothings’ to leaves on a summer’s eve. Like great compositions, the wind may use a caesura, a full stop amid a storm, and in the fragment of silence, I can hear an individual drop of rain fall from a leaf and strike the ground with a fat ‘plop.’ The wind talks. For those who listen, there is much to be learned from the wind.

Farm life wasn’t completely cut off from the larger world. During the 1950s, we depended on AM radio (WCCO-Minneapolis) and the rural telephone to Janesville, six miles away. In those days, the radio gave us farm market reports, ball games, soap operas, the New York Philharmonic concerts, the Jack Benny Show, and CBS News. Static on AM radios also told us more about the weather than the Weather Service. Faint static meant a distant and possible thunderstorm. As static increased in intensity and frequency, so did the storm probability. Our telephone (a wooden box with a crank and speaker) connected us to a party line of 12. We knew who got calls by the pattern of rings. More than that, however, the phone was our Doppler before there was Doppler. In stormy weather, the a ‘ping’ on the phone meant lightning nearby. Frequent ‘pings’ meant the storm was nearly upon us.

We lived about three miles from the former town of St. Mary but only the church remained. In the 1950s, early on Sunday mornings, I heard the peal of its bell as the local Catholics  went to Mass. As the rural population thinned, the diocese closed the church, and it fell victim to time and neglect. I last saw it on a summer evening, shuttered but humming with the sound of bees swarming about a hole in its eaves. Only the cemetery remains but, somewhere in the heavens, the reverberations of that bell continue to ripple toward eternity.

went to Mass. As the rural population thinned, the diocese closed the church, and it fell victim to time and neglect. I last saw it on a summer evening, shuttered but humming with the sound of bees swarming about a hole in its eaves. Only the cemetery remains but, somewhere in the heavens, the reverberations of that bell continue to ripple toward eternity.

It’s a fact that most farmers can tell you the make of tractor solely by its sound. I grew in a neighborhood of green John Deere and red International Harvester models. The Deere’s two-cylinder engines made a distinct ‘pop-pop-pop’ sound and folks called them ‘Johnny Poppers.’ International’s produced a deep, steady growl. We owned small, gray Fords that  purred. Yet, despite the make of tractor, their sound faded quickly with distance. Some of my deepest memories are of twilight on spring evenings, hearing my father whistling Broadway show tunes as he tilled a field for planting. As sure as the sun came up in the east, I knew his restless soul was utterly content and he wanted nothing more than to make the brown, prairie soil ready for seed.

purred. Yet, despite the make of tractor, their sound faded quickly with distance. Some of my deepest memories are of twilight on spring evenings, hearing my father whistling Broadway show tunes as he tilled a field for planting. As sure as the sun came up in the east, I knew his restless soul was utterly content and he wanted nothing more than to make the brown, prairie soil ready for seed.

You may think of the country as a quiet, tranquil place. It is tranquil but never silent. A farm and its countryside are filled with sounds. As a lad, I heard them distinctly because I had few distractions. Each echo, hum, reverberation, crash, jingle, swish, roar, and vibration held meaning. Some brought pleasure, others warned of danger or accompanied pain. Yet each played a part in who I became, and who I know myself to be. Sounds are visceral, indelible, and as much a part of myself as my DNA. Many things combine to make us humans, but I think our individual identities a made, in part, by a distinct sound-cloud of memory and meaning.

Beautiful, Newell. Thank you.

LikeLike

Gracias, Bob. I am in Oaxaca until the end of March and teaching English in the indigenous town of Teotitlan. This is the third year of teaching here in the winter. Sometimes this is a good place to look back and reflect on life in Minnesota.

LikeLike